A short harmony manual for beginners in a hurry.

This very, very condensed page will surely cause an outcry amongst purists, music academy overqualified teachers and other extremists, and I’ll start by offering them my apologies. So many things are obviously lacking, but they would be superfluous during the early years when learning to play; you’ll find here all that’s necessary to free the creative spirit, while never blocking it. All I’m doing is levering open a well-locked door in the hope that some of the visitors to this article – if they are sufficiently interested – will slip through the opening and go on to seek out further specialised information to correct the inevitable “errors” due to this simplification, the “human errors” to which I humbly confess.

Let’s start with some essentials

This paragraph must be learned by heart and its content should become a reflex, otherwise all of your calculations will be false. The notions and the workings of this page are very easy to use once these essentials are mastered.

The basic unit in western music is the TONE, divisible into two SEMI-TONES (Indian music extends to QUARTER TONES).

The space between any two frets on your guitar represents a semi-tone.

The sharp (#) raises the note by a semi-tone.

The flat (b) lowers the note by a semi-tone.

If you look at the display of the following scale, you will see that “sharpening” a natural note (e.g. C) is the equivalent of “flattening” the note that is immediately above.

E.g.: C# = Db, G# = Ab.

NB: as there is only one semi-tone between B and C, one can say to simplify (despite the musical Ayatollahs!!!!) that B# doesn’t exist as the note is in fact C, and that Cb doesn’t exist as it is B. It’s the same for the interval E to F.

Whatever the scale, there is always only a semi-tone between B and C, and between E and F.

The Scales

As it was made clear in the introduction to this page, the aim is not to become a specialist but rather to become capable of constructing a chord and to thus be able to ‘deconstruct’ it to make something new from it, as simply as possible, within a given key. So we’ll cut out the deadwood from the forest and keep only the strict essentials. It will be up to you, after this start, to fight your way through the jungle of the scales that you’ll find on other sites.

We’ll work on two types of scales: the diatonicscale (which can be major or minor and whose notes are specific to the key) and the chromaticscale (which is always the same).

The diatonic scale is made up of a defined sequence of intervals between the notes. It is the succession of these intervals, tones and semi-tones, which determines the major or minor form of the scale. E.g.: C D E F G etc or C D Eb F G etc. We’ll systematically use the scale of C major as our reference; this covers all the white notes on the piano.

The chromatic scale is made up of all the notes, semi-tone by semi-tone. E.g.: C C# D D# E F F# etc. On a piano it uses all the notes, black and white.

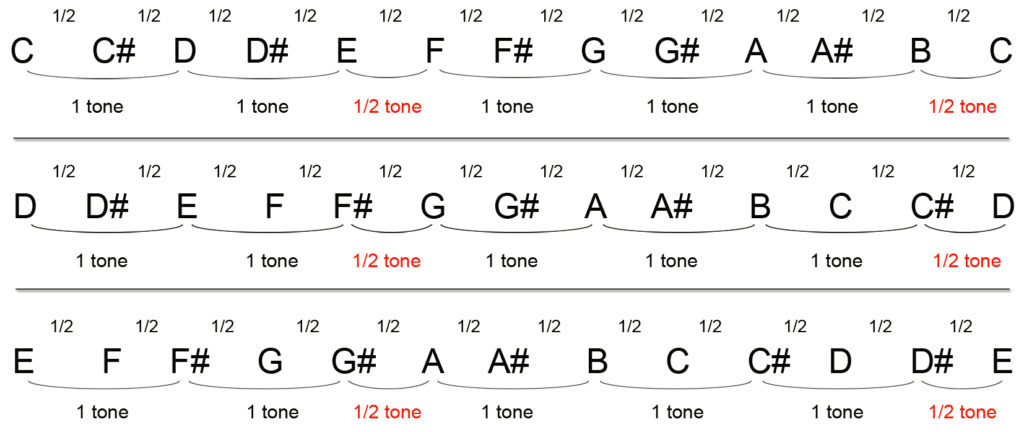

Here’s the plan of a few major scales, with their intervals:

As you can see, there is a whole tone between each two notes EXCEPT between E and F, and between B and C. Quite logically, where there is a whole tone there are two semi-tones (e.g. between C and D).

You’ll also see that for all the major scales (C, D, E

etc) the rising order of the intervals is : 2 (following) tones

– ½ tone – 3 (following)

tones

– ½ tone.

Next to these defined and unchanging intervals,

remember that, for whichever scale you’re in, there is always a semi-tone between E and F, and between B and C.

There are as many scales as there are notes in the scale, each note becoming, in its turn, the ‘fundamental’ of its own scale, the vital thing being to respect the series of intervals (see above the scales of D and E).

The Notes

The notes of the scale are named according

to their ‘height’ or frequency, the vibration of the air measured in Hertz (Hz) (see

the table of frequencies). E.g. : the

unfingered A string is at 110 Hz, the A2 note (G string, finger at the 2nd

fret) is at 220 Hz, the A3 (upper E string, 5the fret) is at 440 Hz.

NB: A1 means the second octave, as

the A0 exists, at 55 Hz. As you can see, at each higher octave, the frequency

is the double of the previous octave.

Everybody knows these names, determined by the height:

A, B, C,

D, E, F, G.

FOR THE CURIOUS

It so happens that the A 440Hz is the dialling tone of the french landline telephones, so you have a free diapason for tuning your A string (which actually is two octaves lower, at 110 Hz).Lower E string = 82.41 Hz

A string = 110 Hz (this is the A1)

D string = 146.83 Hz

G string = 196 Hz

B string = 246.94 Hz

Upper E string = 329.63 Hz

If you wish to know the frequency

of each note over a range of 6 octaves, and in which frequency spread each

instrument is to be found (called the tessitura or range of the

instrument), click here.

The

note names used in France (do, ré, mi, fa, sol, la, si, the reference

note being do which is the C equivalent) were suggested by Gui, a monk

in the Pomposa Abbey, born in Arezzo, Tuscany, near the end of the 10th

century; they are the first syllables of the half-verses of a psalm dedicated

to St John the Baptist, and they are sung on the corresponding notes of the scale:

UTqueant laxis

REsonare fibris

MIra gestorum

FAmuli tuorum

SOLve pollute

LAbii reatum

Sancte Iohannes

The

UT, too muffled a sound and difficult to sing, was replaced in the 18th

century by the randomly-chosen DO.

The

SI (initials of Saint John, Sancte Iohannes) is attributed to the french

composer Le Maire.

The notes also carry names with relation to their place in the scale.

These are called degrees. They are placed on a ladder, semi-tone by semi-tone, and correspond to the chromatic scale.

It is vital to learn them by heart and in the right order as you will construct your chords with them.

Fundamental

Minor second

Major second

Minor third

Major third

FourthDiminished fifth

Fifth

Augmented fifth

SixthMinor seventh

Major seventh

Octave

Diminished ninth

Ninth

Augmented ninth

The next others will not be useful to you for quite a long time to come.